Some time ago, I wondered why God was dissatisfied with Cain's offering. John Paul II provided some insight as I noted here. The June 2012 Magnificat offers more insight from Saint Ephrem the Syrian. He writes:

Abel was very discriminate in his choice of offerings, whereas Cain showed no such discrimination. Abel selected and offered the choicest of his first born and of his fat ones, while Cain either offered young grains or [certain] fruits that are found at the same time as the young grains. Even if his offering had been smaller than that of his brother, it would have been as acceptable as the offering of his brother, had he not brought it with such negligence. They made their offerings alternately; one offered a lamb of his flock, the other the fruits of the earth. But because Cain had taken such little regard for the first offering that he offered, God refused to accept it in order to teach Cain how he was to make an offering. For Cain had bulls and calves and an abundance of animals and birds that he could have offered. But he offered none of these on that day when he offered the first fruits of his land.

What would have been the harm if he had brought ripe grains or if he had chosen the fruits of his best trees? Although this would have been easy, he did not do even this. It was not that he had other intentions for his best grains or his best fruits; it was that, in the mind of the offerer, there was no love for the one who would receive his offering. Therefore, because Cain brought his offering with negligence, God despised it on that account, lest Cain think either that God did not know of Cain's negligence, or that God preferred the offerings rather than those who were offering them.

From: St. Ephrem the Syrian: Selected Prose Works, The Fathers of the Church, Vol. 91, 1994, CUA Press.

Tuesday, August 7, 2012

Monday, April 16, 2012

Psalms

Reading the book of Psalms was only slightly more edifying than reading about the psalms. In fact, I may have gotten more out of the latter.

It helped to know that the psalms, essentially prayers in poetic form, number 150 and that they can be divided into five books as follows: Psalms 1-42, 43-72, 73-89, 90-106 and 107-150. The first two books are psalms or prayers related to King David's reign. The last division includes the Songs of Ascents, Psalms 120-134, heretofore completely unknown to me. Psalm 119 has to be the longest psalm and was probably at one time the final psalm before others were added to the book. Most were probably written around 1,000 B.C. or after the Babylonian exile. The authors of the psalms are largely unknown.

The majority of the psalms express cries for help (laments), including somewhat anguished pleas for relief from persecution and unjust accusations, release from suffering at the hands of the wicked and relief from physical pain. They read as personal cries for help, but can also be interpreted as cries on behalf of Israel as a nation. There are psalms of praise and thanks as well and also psalms of 'enthronement.'

The psalms came a bit more alive for me as I noted the various instructions included in the preface to many of the psalms. There was an awful lot of singing and music-making going on in the worship of the ancient Hebrews. I really had never fully grasped that the psalms were written to be sung and to have musical accompaniment. My study bible was always careful to provide an explication for these notes and I've chosen to collect them here:

Asaph: one of Kind David's chief musicians

Gittith: a kind of melody, hence the notation "according to the Gittith"

Jeduthun: one of David's musicians

Korahites: temple singers

Lilies: a melody, hence "according to the Lilies"

Maskil: an artful song, as in artistically composed but still with a instructive message

Muth-labben: musical notation of some kind

Miktam: perhaps a psalm inscribed on a stone wall, hence "a Miktam of David"

Selah: a liturgical or musical direction

Sheminith: a liturgical or musical direction, probably meaning the eighth instrument? and so "according to the Sheminith"

Shiggaion: a lament (and a term I coincidentally heard just recently in a discussion of a contemporary mid-Eastern band)

To the leader: the leader being the musical director and so an instruction to him

I note here some favorite psalms, almost always more beautiful in their King James Version than any other: 8, 21, 22,23 (of course!), 24, 37, 51, 56, 67, 74, 79, 94, 100, 104, 121, 139

It helped to know that the psalms, essentially prayers in poetic form, number 150 and that they can be divided into five books as follows: Psalms 1-42, 43-72, 73-89, 90-106 and 107-150. The first two books are psalms or prayers related to King David's reign. The last division includes the Songs of Ascents, Psalms 120-134, heretofore completely unknown to me. Psalm 119 has to be the longest psalm and was probably at one time the final psalm before others were added to the book. Most were probably written around 1,000 B.C. or after the Babylonian exile. The authors of the psalms are largely unknown.

The majority of the psalms express cries for help (laments), including somewhat anguished pleas for relief from persecution and unjust accusations, release from suffering at the hands of the wicked and relief from physical pain. They read as personal cries for help, but can also be interpreted as cries on behalf of Israel as a nation. There are psalms of praise and thanks as well and also psalms of 'enthronement.'

The psalms came a bit more alive for me as I noted the various instructions included in the preface to many of the psalms. There was an awful lot of singing and music-making going on in the worship of the ancient Hebrews. I really had never fully grasped that the psalms were written to be sung and to have musical accompaniment. My study bible was always careful to provide an explication for these notes and I've chosen to collect them here:

Asaph: one of Kind David's chief musicians

Gittith: a kind of melody, hence the notation "according to the Gittith"

Jeduthun: one of David's musicians

Korahites: temple singers

Lilies: a melody, hence "according to the Lilies"

Maskil: an artful song, as in artistically composed but still with a instructive message

Muth-labben: musical notation of some kind

Miktam: perhaps a psalm inscribed on a stone wall, hence "a Miktam of David"

Selah: a liturgical or musical direction

Sheminith: a liturgical or musical direction, probably meaning the eighth instrument? and so "according to the Sheminith"

Shiggaion: a lament (and a term I coincidentally heard just recently in a discussion of a contemporary mid-Eastern band)

To the leader: the leader being the musical director and so an instruction to him

I note here some favorite psalms, almost always more beautiful in their King James Version than any other: 8, 21, 22,23 (of course!), 24, 37, 51, 56, 67, 74, 79, 94, 100, 104, 121, 139

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Job

I began reading the Book of Job under the assumption that Job was a virtuous soul who refused to blame God for his misfortunes and that he remained steadfastly faithful to the Lord despite the fact that his friends tried to convince him that his loyalty to God was in vain. Not quite.

I consulted Garrison who breaks the Book of Job into four-chapter segments and provides explication. I did a second reading and afterwards felt on firmer ground. Following is a mix of themes highlighted by Garrison and my own take-aways after the second reading.

Job, though a believer, has a touch of the rebel in him. He's a bit of a cynic. A fatalist. It's all for naught so why bother. He's good so why has life gone bad? Though he remains faithful to God, his understanding of the ways of the Lord fall short of the mark. He seems to feel God has deserted him and perhaps fails to understand that God is not responsible for the misfortune that has befallen him.

A central theme of the book is expressed in Ch.4, 17 and again in Ch. 25. Can mortals be righteous before God? Do we achieve righteousness through striving or is it an unearned gift from God?

Why does God bother about us?

The Deuteronomistic notion that evil is punished and virtue is rewarded is too simplistic. Job is correct in this view unlike his friends who persist in this belief.

If it's impossible for man to be perfect, why bother trying to be good? We all just end up on the dust heap regardless. What's the meaning of life anyway? "My days are swifter than a weaver's shuttle, and come to their end without hope." (Ch 7,6)

Job is angry at God (Ch 21-25).

Job says God is persecuting him (Ch 26-28). Doesn't he know about Satan?

While it is true that Job doesn't denounce God, he really does think that God is responsible for his misery. He just can't figure out why God has let this happen given that he, Job, is such a great guy (Ch 29-31).

Finally Elihu appears (Ch 32-38) and sheds some light on the controversy between Job and his friends. Elihu more or less denounces Job as without faith in or understanding of God and accuses Job of blabbering endlessly without making any sense. Elihu points out (finally someone does) that God can't do wrong. In Ch 36, 11-13, Elihu seems to be saying that obedience to God is what matters, not whether one is good or evil. Might he also be saying that Job is too concerned with revenge on evil-doers and their judgment rather than with making sure that he is right before God (Ch 36, 17).

One part that wasn't difficult to understand was the conclusion of the book when God addresses Job. This language was quite dramatic with vivid and graphic imagery.

A couple hazy areas remain. Why does God scold Job and then praise him? And, how in the world does Elihu come to know all that he knows?

I consulted Garrison who breaks the Book of Job into four-chapter segments and provides explication. I did a second reading and afterwards felt on firmer ground. Following is a mix of themes highlighted by Garrison and my own take-aways after the second reading.

Job, though a believer, has a touch of the rebel in him. He's a bit of a cynic. A fatalist. It's all for naught so why bother. He's good so why has life gone bad? Though he remains faithful to God, his understanding of the ways of the Lord fall short of the mark. He seems to feel God has deserted him and perhaps fails to understand that God is not responsible for the misfortune that has befallen him.

A central theme of the book is expressed in Ch.4, 17 and again in Ch. 25. Can mortals be righteous before God? Do we achieve righteousness through striving or is it an unearned gift from God?

Why does God bother about us?

The Deuteronomistic notion that evil is punished and virtue is rewarded is too simplistic. Job is correct in this view unlike his friends who persist in this belief.

If it's impossible for man to be perfect, why bother trying to be good? We all just end up on the dust heap regardless. What's the meaning of life anyway? "My days are swifter than a weaver's shuttle, and come to their end without hope." (Ch 7,6)

Job is angry at God (Ch 21-25).

Job says God is persecuting him (Ch 26-28). Doesn't he know about Satan?

While it is true that Job doesn't denounce God, he really does think that God is responsible for his misery. He just can't figure out why God has let this happen given that he, Job, is such a great guy (Ch 29-31).

Finally Elihu appears (Ch 32-38) and sheds some light on the controversy between Job and his friends. Elihu more or less denounces Job as without faith in or understanding of God and accuses Job of blabbering endlessly without making any sense. Elihu points out (finally someone does) that God can't do wrong. In Ch 36, 11-13, Elihu seems to be saying that obedience to God is what matters, not whether one is good or evil. Might he also be saying that Job is too concerned with revenge on evil-doers and their judgment rather than with making sure that he is right before God (Ch 36, 17).

One part that wasn't difficult to understand was the conclusion of the book when God addresses Job. This language was quite dramatic with vivid and graphic imagery.

A couple hazy areas remain. Why does God scold Job and then praise him? And, how in the world does Elihu come to know all that he knows?

Esther

What a great story! Who would not like Esther! She's a thoroughly engaging heroine--beautiful and capable with considerable power, but not brassy or pushy, always humble and loyal.

Years ago in the Presbyterian church, we studied this book and the young, female seminarian teaching the class seemed to be guiding us toward an interpretation of Esther as a feminist (sigh). When I offered during the class that I thought Esther could be described, in a word, as obedient, our seminarian recoiled in mild disgust. Oh well.

Esther is anything but a feminist. She didn't compete with the men around her, she didn't take on masculine ways to achieve her ends and she didn't try to take every man down a peg or two (except for the odious Haman who deserved what he got). She faithfully obeyed her cousin Mordecai and her foreigner husband while simultaneously serving God and her people.

The lack of any mention of God in the Book of Esther never seemed problematic to me, but for comparison, I read the Greek version of Esther which my study Bible includes. That the Greek version reads so smoothly could be taken as an indication that God is without question the force behind all that goes on in the story of Esther. From what mere earthly power could Mordecai and Esther, Jews in a foreign land, have possibly summoned up the courage and resolve to plead for the lives of their people?

Years ago in the Presbyterian church, we studied this book and the young, female seminarian teaching the class seemed to be guiding us toward an interpretation of Esther as a feminist (sigh). When I offered during the class that I thought Esther could be described, in a word, as obedient, our seminarian recoiled in mild disgust. Oh well.

Esther is anything but a feminist. She didn't compete with the men around her, she didn't take on masculine ways to achieve her ends and she didn't try to take every man down a peg or two (except for the odious Haman who deserved what he got). She faithfully obeyed her cousin Mordecai and her foreigner husband while simultaneously serving God and her people.

The lack of any mention of God in the Book of Esther never seemed problematic to me, but for comparison, I read the Greek version of Esther which my study Bible includes. That the Greek version reads so smoothly could be taken as an indication that God is without question the force behind all that goes on in the story of Esther. From what mere earthly power could Mordecai and Esther, Jews in a foreign land, have possibly summoned up the courage and resolve to plead for the lives of their people?

Judith

I almost skipped over this book entirely. I was just getting the dates, events, kings and other characters of the pre and post-exilic period straight only to read that the book of Judith is a jumble of historical inaccuracies of that time, a book not intended to be read as historical fact.

Fortunately, however, I skimmed around and landed on Ch. 8 where the real action begins. Judith is an intriguing personality, an imperious sort, a commanding presence you might say. She's intrepid and plucky, certainly not afraid to get her hands dirty as you can see above. But she does all this without sacrificing her femininity, a good counter-culture role model for the politically feminized woman of today.

Fortunately, however, I skimmed around and landed on Ch. 8 where the real action begins. Judith is an intriguing personality, an imperious sort, a commanding presence you might say. She's intrepid and plucky, certainly not afraid to get her hands dirty as you can see above. But she does all this without sacrificing her femininity, a good counter-culture role model for the politically feminized woman of today.

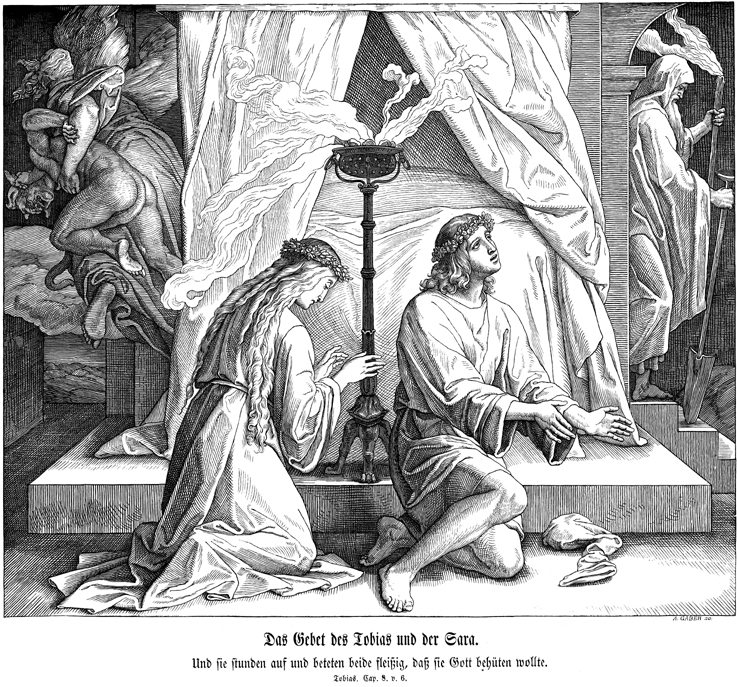

Tobit

The events in in the Book of Tobit occur after the fall of Israel to the Assyrians in 722 B.C., but the book is thought to have been written around 200 B.C. This book, as well as those of Judith and Esther, gives some insight into the life of the Israelites in exile. Tobit himself was carried off to the Assyrian capital of Nineveh where he remained a devout and observant Jew. In the Jewish Bible, these books are considered to be history or 'writings,' yet they aren't historical in any strict sense of the word; Baker suggests that they're wisdom literature because they instruct in practical matters concerning faith and daily life. (However, note that the wisdom literature proper begins with Job.)

The events in in the Book of Tobit occur after the fall of Israel to the Assyrians in 722 B.C., but the book is thought to have been written around 200 B.C. This book, as well as those of Judith and Esther, gives some insight into the life of the Israelites in exile. Tobit himself was carried off to the Assyrian capital of Nineveh where he remained a devout and observant Jew. In the Jewish Bible, these books are considered to be history or 'writings,' yet they aren't historical in any strict sense of the word; Baker suggests that they're wisdom literature because they instruct in practical matters concerning faith and daily life. (However, note that the wisdom literature proper begins with Job.)The tale of Tobit is a good one (though not as good as the story of Esther), and I became quite invested in knowing what exactly would come of the marriage between Tobit's son, Tobias, and the bewitched Sarah. Like Ruth and Boaz, Tobias and Sarah have a redemptive and refining effect on one another and their respective families. Through her marriage to Tobias, the unfortunate Sarah is finally rid of the demon, Asmodeus, that killed her seven (that's 7) previous husbands. And through his obedience to his father (and his guardian angel!), Tobias is able to help expunge the demon from Sarah and then restore his father's eyesight. Both Sarah and her now-father-in-law Tobit gain a new desire to live because of the marriage of Sarah and Tobias. The angel adds to the mystery and suspense in the story and lends a bit of a fairy tale flavor as does the strange fish that provides the needed cleansing potions.

Monday, February 6, 2012

Ezra and Nehemiah

The book of Ezra was most likely written around 400 BC, its author thought to be the same as that of both books of Chronicles and also Nehemiah.

The book of Ezra was most likely written around 400 BC, its author thought to be the same as that of both books of Chronicles and also Nehemiah. Reading both Ezra and Nehemiah (and the Book of Esther as well) helps to better understand the Babylonian exile although the question still lingers in my mind as to why the Babylonians deported the Hebrews and took them to Babylon. What did they do with them once everyone was rounded up in Babylon? It appears they took more or less the upper crust of administrators, priests, temple officials and city inhabitants, leaving behind the hunters, gatherers and those inhabiting the fields and countryside. Was there some reason Nebuchadnezzar didn't just kill everyone off when his armies destroyed the temple? It was maybe preferable to have more physical bodies to count as part of the Babylonian empire?

Ezra is identified variously as a scribe, a priest and a priest but not a Levite (not all priests are Levites I presume?). He's sent by either Ataxerxes I or II to Jerusalem to check up on how the pentateuchal law was being administered there. If sent by the former, the year of Ezra's visit was 458 BC. If sent by the latter, the year of his visit was 358 BC. He seems to have taken mostly males with him, carefully chosen and named in Ch. 8.

One question that comes to mind is why Ataxerxes would care what was going on in Jerusalem and send Ezra on this mission. After all, I assume that Ezra or anyone else would have been free to take on this project on their own as of 539 BC when Cyrus ended their exile.

After the postponement of the re-building of the temple due to objections on the part of non-Jewish groups in the region, the Persian king, Darius, issued a decree directing that the re-building of the temple should proceed. The temple reconstruction was completed during Darius's reign in the year 515 B.C. Why is he supportive? As the notes in my Bible read: "It is said that this is the first time in recorded history that a ruler not only approved the practice of a foreign religion in his empire but also devoted state resources to its maintenance."

The general problem that Ezra had to address in Jerusalem was the falling-away from the faith to which many post-exilic Jews had succumbed. One of the thornier problems was the matter of Hebrews having married foreign wives upon their return. The rather unpalatable, even draconian, solution to the problem was the deportation of foreign wives and children.

If Ezra handled the religious rebuilding of Jerusalem and Judah, Nehemiah handled the administrative, governmental side. His tenure is from 445-433 B.C and he's described by my Bible as a "Jew who had risen to high office in the Persian administration." Nehemiah presided over the re-building of the wall surrounding Jerusalem. The ceremony surrounding the dedication of the wall is good reading, and, overall, it would be worth reading these two books again just to get a practical perspective on post-exilic Israel.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)